Would you describe your school as a ‘thinking school’: one that highlights the importance of critical thinking as an essential part of learning?

Too often we hear dismay over a school system that values grades over growth and product over process. So, when I recently attended a ‘Thinking Maps’ training day I listened with interest to the stories of schools who use tools to explicitly highlight the thought processes involved in learning.

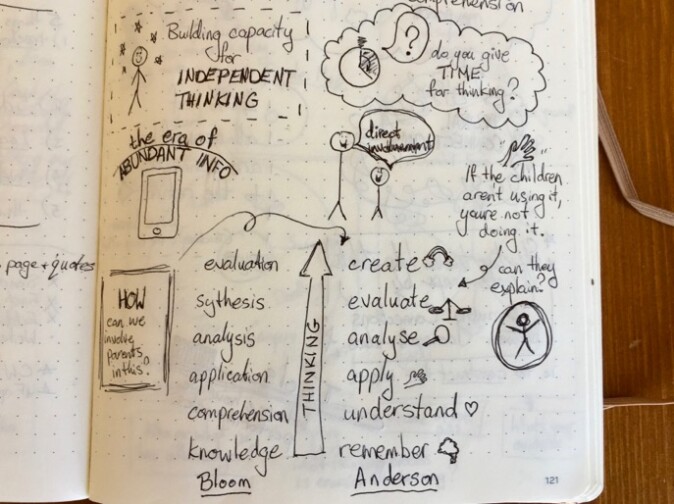

You may be familiar with Bloom’s taxonomy – a structure for examining the hierarchy of thinking skills. Anderson’s framework adopts a similar structure, but with some more child-friendly verbs. Teaching this sequence enables children to have ownership of their learning: to be aware of their thinking processes and have the words to talk about this.

The intention with Thinking Maps is to establish a shared visual language for critical thinking. I’ve always been interested in how sketching provides a visual hook for conversation.

As much of my work involves talking, it’s useful to establish a visual structure during conversations, to clarify our focus and capture offhand comments to return to later. Even in their scruffiest form these sketches serve as a valuable visual record of a session, which I often refer back to in conjunction with my formal case notes.

There’s a great deal of value in adding visual elements to learning. I reject the idea that ‘some people are visual learners’. This isn’t about learning ’style’. If you can see, you’re a visual learner. I have yet to come across anyone who says ‘Please don’t show me; I’m an auditory learner.’

Thinking Maps consists of 8 key structures that encapsulate key thought processes: gathering ideas, comparing, sequencing, categorising and many more.

Each map has a corresponding hand gesture; a seemingly small detail with great value. Within our large group discussions the hand gestures were a useful way for the leader to cue us in to the focus of discussion and it was a quick way for the learners to demonstrate their own thinking.

So, how will I apply Thinking Maps to my own practice? Well, the course suggested introducing each of the maps with an autobiographical element. I certainly using autobiography tools (like ‘Your Perfect Day’) to get to know children and understand their priorities and motivations, so I can see this fitting neatly in to my practice.

I’ll certainly use the sequencing map to support work on narrative skills. I’m excited by the potential of using large pieces of paper for some of my smaller children, to use real objects in conjunction with the maps. The course facilitator suggested that this type of visual language could be introduced at any age, so I plan to experiment and explore its potential.

Huge thanks to Gaby Harris, a fellow SaLT, for organising this event with Thinking Schools International.